Where is the firehose of data we were promised?

Where is the firehose of data we were promised?

Access to personal health data is the foundation requirement for any movement toward patient engagement. Don’t get me wrong, access to the data itself will not solve any problem. In fact, in the early stages, access to vast amounts of personal health data will probably create a lot more problems than it solves. However, with widespread access to personal health data, enterprising entrepreneurs will have the keys to provide users with highly customized and personalized health-related experiences, or such is the much hyped promise of Health 2.0. And when I say access, I am talking about simple and seamless access to my data. I recently tried to link my Google Health account to Walgreens Pharmacy. It took 8 minutes to complete a profile at Walgreens.com, and I still did not get my data. It took another few days for the data to drop into GHealth. I am pretty sure I clicked a release allowing Google to send a fax to Walgreens for permission. That would be pretty funny if it wasn’t so sad. Call me lazy, but I think I deserve an OAuth for my data, where, as a user, I simply need to provide permission and credentials. Then let the app do the rest.

Given the current state of access to health data, most ‘successful’ Health 2.0 companies are limited, and will continue to be limited, to very early adopters. Health 2.0 will not succeed on any meaningful scale as long as apps require users to input their own health data to receive a service in return. Most users are not that motivated (some might even say lazy like me), most do not have access to their information and many do not feel comfortable enough with the data to use it. The watershed for Health 2.0 will come when big data starts to flow effortlessly into consumers hands in huge chunks.

The Data Watershed: E-Prescribing and Medication History

Fortunately, I think this data watershed may be coming. Today, there are only a few sources of big data in healthcare. Data is captured in medical charts (or EMRs for the select few), it is captured in medical claims databases and it is captured as prescription drug histories.

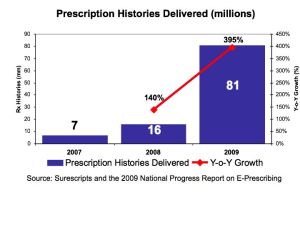

Due to the rise in e-prescribing, the first of these firehoses of data to reach patients will probably be prescription drug histories. E-prescribing is pumping digital data into the system in large and growing quantities. And in March 2010, Google Health announced a partnership with Surescripts, the largest e-prescribing network in the US, to make it possible for millions of users to access to their medication histories.

The Importance of Medication History

So, what’s the a big deal? Medication history is only one small part of the complete data package, right? Wrong. Medication history is the backbone of a patient’s medical history, and, for better or for worse, pharmaceutical use is the foundation of our current medical system. In the vast majority of cases, when a patient gets sick, they go to the doctor, get diagnosed, and get a prescription. So a patient’s medication history gives a detailed, longitudinal medical history for the patient. One just needs to know how to translate it.

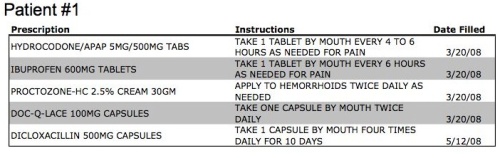

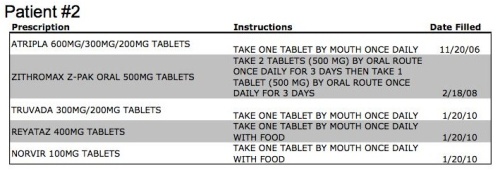

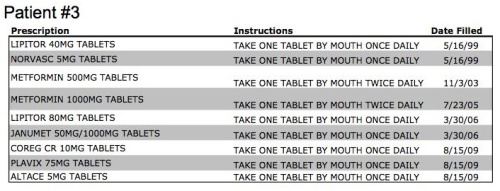

Below are a few examples showing simplified medication histories for three hypothetical patients. Let’s see what we can learn about these patients from these simple data points.

At first glance, patient #1 has a pretty random assortment of medications, including some pain medications, a prescription stool softener (Doc-Q-Lace), a 4 times a day antibiotic and hemorrhoid medication. But any woman who has given birth probably recognizes this assortment of medications as a pretty typical post-childbirth discharge list. All of these meds prescribed on 3/20/08 tells us that this is a woman of childbearing age who gave birth on 3/18/08 +/- 2 or 3 days. We also know from the Diclo antibiotic that she breastfed her child for at least 2 months, and had mastitis, a common breast feeding infection. I bet that Diapers.com would like this information. Or possibly Mattel, knowing that this woman now has a two year old child? How about the entrepreneur who is developing the next BabyCenter.com app for new moms?

Patient #2 has a pretty straight-forward and easily identifiable medical history. The point of this example is to show the depth of personal information that can be derived from five simple data points. We know that this patient is HIV positive and began treatment at the end of 2006. We also know that they are probably not doing well, as they have recently failed on their first-line antiretroviral therapy and have progressed to second-line treatment with a protease inhibitor (Reyataz). We can also make some assumptions, based on demographics, and assume there is about a 75% chance this patient is male and make assumptions on age. I would have to assume that this patient would want to strictly control who has access to these five data points.

Patient #2 has a pretty straight-forward and easily identifiable medical history. The point of this example is to show the depth of personal information that can be derived from five simple data points. We know that this patient is HIV positive and began treatment at the end of 2006. We also know that they are probably not doing well, as they have recently failed on their first-line antiretroviral therapy and have progressed to second-line treatment with a protease inhibitor (Reyataz). We can also make some assumptions, based on demographics, and assume there is about a 75% chance this patient is male and make assumptions on age. I would have to assume that this patient would want to strictly control who has access to these five data points.

Patient #3 is a little more complicated, but is a pretty typical patient with cardiovascular disease. We know this patient has high cholesterol (Lipitor), high blood pressure (Norvasc) and type 2 diabetes (Metformin). We know from the pretty rapid intensification in oral anti-diabetic therapy (Metformin 500 to Metformin 1000 to Janumet, which is a combination of Metformin and Januvia) that this patient’s diabetes is less well controlled than the average type 2 diabetic. We also know their high cholesterol is unconrolled on a standard dose of Lipitor, due to the increase to Lipitor 80. The addition of Coreg (a beta-blocker), Plavix (an anti-platelet drug) and Altace (an ACE inhibitor), all on August 15, 2009, leads us to believe that this patient had a major cardiac event, most likely a heart attack requiring percutaneous intervention (PCI) and a stent to open a clogged coronary artery, as this list is a pretty common myocardial infarction discharge list. What else can we infer from this data? We can be pretty sure this patient has good health insurance, and if they are on Medicare, they are probably in a Medicare Advantage plan, due to the number of branded medications and lack of generic substitution (i.e. generic simvastatin vs. branded Lipitor).

Patient #3 is a little more complicated, but is a pretty typical patient with cardiovascular disease. We know this patient has high cholesterol (Lipitor), high blood pressure (Norvasc) and type 2 diabetes (Metformin). We know from the pretty rapid intensification in oral anti-diabetic therapy (Metformin 500 to Metformin 1000 to Janumet, which is a combination of Metformin and Januvia) that this patient’s diabetes is less well controlled than the average type 2 diabetic. We also know their high cholesterol is unconrolled on a standard dose of Lipitor, due to the increase to Lipitor 80. The addition of Coreg (a beta-blocker), Plavix (an anti-platelet drug) and Altace (an ACE inhibitor), all on August 15, 2009, leads us to believe that this patient had a major cardiac event, most likely a heart attack requiring percutaneous intervention (PCI) and a stent to open a clogged coronary artery, as this list is a pretty common myocardial infarction discharge list. What else can we infer from this data? We can be pretty sure this patient has good health insurance, and if they are on Medicare, they are probably in a Medicare Advantage plan, due to the number of branded medications and lack of generic substitution (i.e. generic simvastatin vs. branded Lipitor).

The Good and Bad of Medication History

I believe widespread access to medication histories will infuse new life into Health 2.0 and the entrpreneurs working in this field. Any of these entrepreneurs not actively thinking about how to use medication histories in their apps are missing the boat. With easy access to medication history, users can give permission for App X to access their medication history (hopefully with one click), and receive highly personalized services in return. Keas is beginning to do this with taylored Care Plans, but I am waiting for the apps that look at my medication history and tell me other drugs I can take (to save money), whether my physician is following guidelines, news I should read, and FDA alerts I should know about. I am waiting for the app that connects me to similar patients based on our medication histories, the app that looks at my history and asks simple, taylored questions to help me further populate a more robust PHR, and the app that pays me to allow pharma companies to see my de-identified medication history and ask me questions about my data (pharma loves medication history information, just ask IMS Health, which recently sold for $5.2 billion).

But, of course, with this much personal data coming into the mix so quickly, there are significant privacy risks coming too. The same algorithms used to translate a medication history into a health profile for customized applications can also be used by others to learn deeply personal facts about individuals. So, with all the good that will come from access to medication histories, the first major privacy breaches and big scare stories are probably coming as well. Get ready, the Health 2.0 ride is getting more interesting.